RD-E: 1101 Elasto-plastic Material Law Characterization

The purpose of this example is to introduce a method for characterizing and validation of the most commonly used Radioss material laws for modeling elasto-plastic materials.

The use of "engineering” and "true” stress-strain curves is pointed out. Failure models are also introduced to better fit the experimental response.

Options and Keywords Used

- Shell elements

- Isotropic elasto-plastic Johnson-Cook material (/MAT/LAW2 (PLAS_JOHNS))

- Isotropic elasto-plastic material (/MAT/LAW36 (PLAS_TAB))

- Necking point, maximum stress, and failure criteria

- Boundary conditions (/BCS)

- Imposed velocities (/IMPVEL)

- Material definition (Materials)

- Moving Frame (/FRAME/MOV)

- Nodal time step (/DT/NODA/CST)

- H3D animation output (H3D Output)

- Experimental results (Steel DP600 1)

Input Files

Model Description

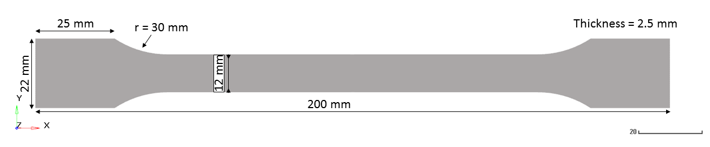

Tension is applied to an object. The standardized “dogbone" object contains a defined cross-sectional area . The material to be characterized is DP600 Steel. 1 A velocity is imposed at the right-end.

Figure 1. Geometry of the Standardized Tensile Object. with a defined cross-sectional area

The material undergoes isotropic elasto-plastic behavior which can be reproduced by a Johnson-Cook (/MAT/LAW2). The tabulated material law (/MAT/LAW36) is also studied.

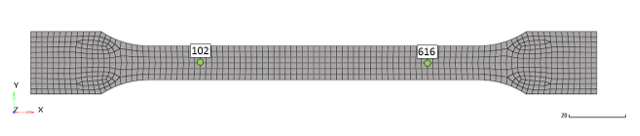

The model is meshed with 4-node shells and 3-node shells as shown in Figure 2. The average element size is about 2 mm.

- 5 integration points over the thickness.

- QEPH shell formulation (Ishell = 24).

- Iterative plasticity for plane stress (Newton-Raphson method; Iplas = 1).

- Thickness changes are considered in stress computation (Ithick = 1).

- Initial thickness is uniform, equal to 2.5 mm

Boundary Condition

Figure 2. All Boundary Conditions Applied to the Tensile Test Model

Two measurement nodes with a distance of 80 mm are chosen (Figure 3) to continuously measure the change in length in the measurement section of the sample during the simulation and to obtain the strain on the sample.

- Measure force

- Cross-sectional area of the undeformed sample

- Change in length between the two measurement points

- Initial length of the measurement section

Figure 3. Measurement Nodes with a Distance of 80 mm

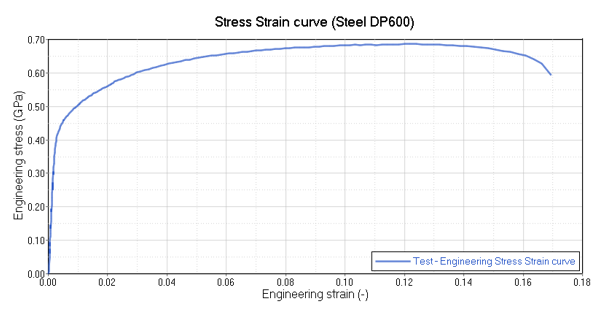

Figure 4. Experimental Results of a Tensile Test of a DP600 Steel Object

Characterization of the Material Law

There are two steps to characterize the material law.

Transform the engineering stress versus engineering strain curve into a true stress versus true strain curve (this step applies to any elasto-plastic material law).

Extract the main parameters from the true stress versus true strain curve, to define the material law (Johnson-Cook law and material coefficients for /MAT/LAW2 or the yield curve definition for /MAT/LAW36).

When there is no material test data available (for example, in an early design stage), values of Yield stress, Ultimate tensile strength (engineering stress value) and Engineering strain at UTS must be provided to characterize /MAT/LAW2 using Iflag = 1.

The characterization will be made for /MAT/LAW2 (Johnson-Cook elasto-plastic), and /MAT/LAW36 (tabulated elasto-plastic). For each of the material laws, the yield stress and Young's modulus are determined from the curve.

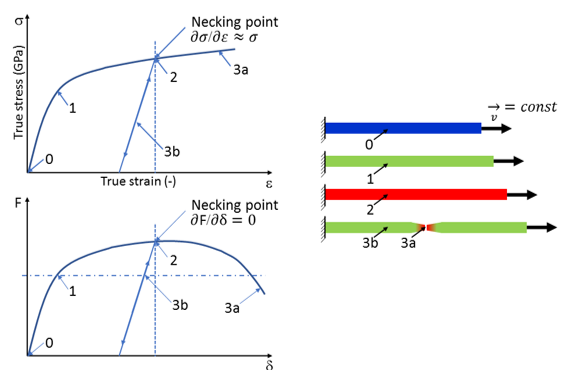

Figure 5. Tensile Test Schematic. (0 - 1= elastic region; 1= yield point; 2= necking point; 3a= fracture; 3b= linear elastic relaxation)

| Material Property | Generic Equation |

|---|---|

| Engineering stress | |

| Engineering strain | |

| True stress | |

| True strain | |

| True strain rate |

Results

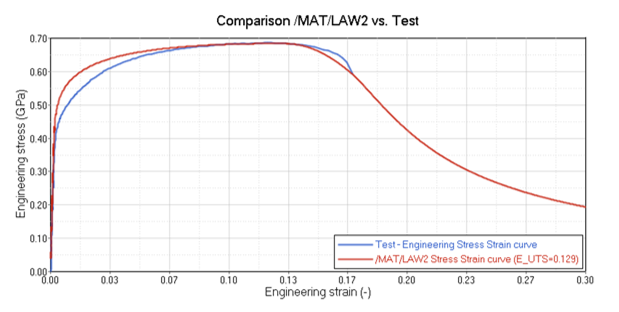

/MAT/LAW2: Elasto-plastic Material Law using the Johnson-Cook Model

- Yield stress and is read from the experimental curve

- and

- Material parameters

If the material parameters and are not available, then Radioss can use /MAT/LAW2, Iflag = 1. In this case, the UTS (Ultimate tensile strength, engineering value) and engineering strain at UTS are entered. These values can often be found online, in literature or from a material supplier. Radioss will then calculate the and parameters used in Equation 10.

- Data

- Value

- Yield stress

- 0.3 GPa

- UTS

- 0.686 GPa

- Strain at UTS (E_UTS)

- 0.129 (12.9%)

Since the simulation calculates true stress and true strain for the elements, the engineering stress-strain curve from the simulation must be calculated. Similar to the test, the engineering stress can be calculated by using Equation 1 and the rigid body force and original area. The engineering strain can be calculated by using Equation 2 and the displacement between the two measurement nodes and the original distance. In the model, the displacement of node 616 is measure with respect to the displacement of node 102 by using a local moving system placed at node 102. This allows the displacement between the two nodes to be output as the displacement of node 616.

Figure 6. Comparison of Results using /MAT/LAW2 and the Test

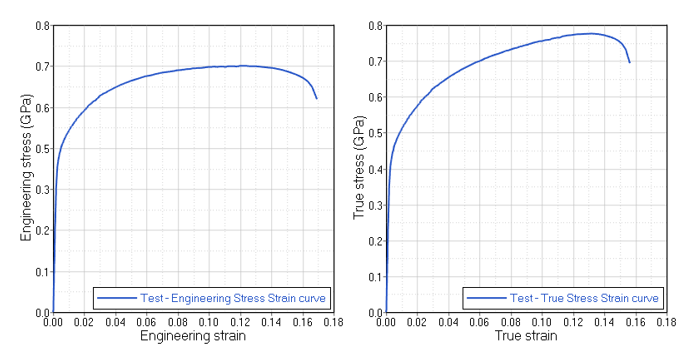

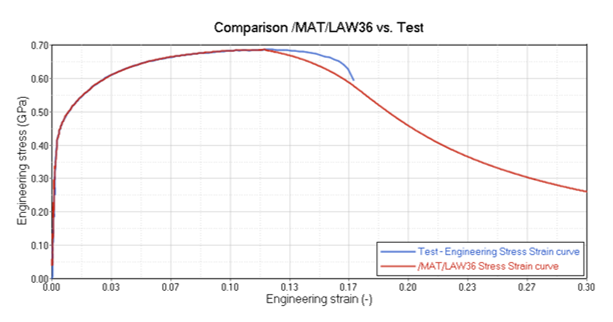

/MAT/LAW36: Elasto-plastic Material Law using a Tabulated Input Function

Figure 7. Engineering Stress versus Strain Compared to True Stress-Strain, Experimental Data

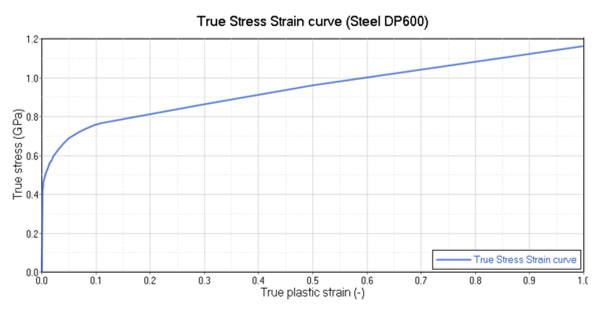

The necking point is where the slope of the engineering stress-strain curve becomes zero. All values after the necking point can not be used for creating the material curve for /MAT/LAW36 and can be removed from the data and disregarded. Values after the necking point must be extrapolated to a strain larger than failure for the material. The necking point occurs at the engineering strain at the ultimate tensile stress = 0.129. After this point, the curve was linearly extrapolated to 100% plastic strain as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. True Stress versus True Plastic Strain Curve Extrapolated to 100%

Figure 9. Comparison of the Simulation Results of the Tensile Test with /MAT/LAW36 versus Test

/FAIL/BIQUAD: Simplified Nonlinear Strain-based Failure Criteria with Linear Damage Accumulation

In some elasto-plastic material models, a single plastic strain at failure can be input to model material failure. The element is deleted when the plastic strain reaches a user-defined value .

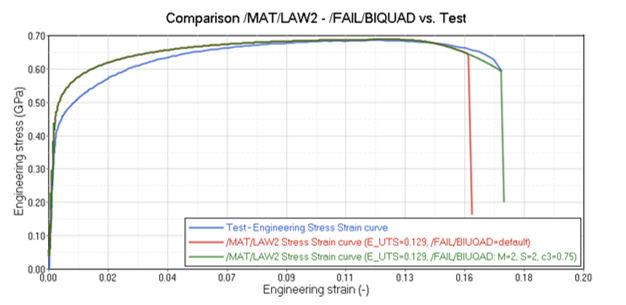

- /MAT/LAW2 with /FAIL/BIQUADWhen the default high strength steel (HSS) values (M_flag =2) included in /FAIL/BIQUAD are used, the simulation shows failure before the test. To better match the test, the /FAIL/BIQUAD uniaxial tension plastic strain at failure value (c3) is increased from 0.5 to 0.75. Figure 10 shows the results for both simulation cases.

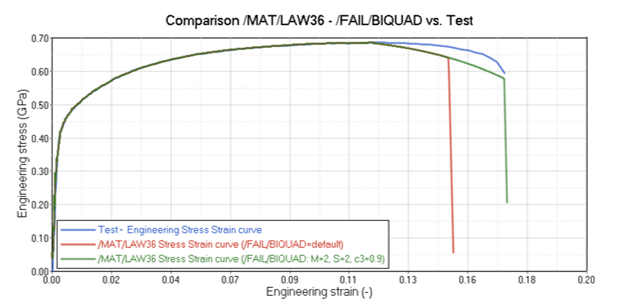

Figure 10. Comparison of Simulation Results of Tensile Test: /MAT/LAW2 with /FAIL/BIQUAD versus Test - /MAT/LAW36 with /FAIL/BIQUADSimilar to the LAW2 simulation, the /FAIL/BIQUAD uniaxial tension plastic strain at failure value (c3) is increased from 0.5 to 0.9 so that the failure point in the simulation matches the test.

Figure 11. Comparison of Simulation Results of Tensile Test: /MAT/LAW36 with /FAIL/BIQUAD versus Test

Conclusion

In the first part of the example, a method was introduced to characterize and validate the most commonly used Radioss material laws. The /MAT/LAW2 (PLAS_JOHNS) material was used with a few material parameters to represent the material. The /MAT/LAW36 (PLAS_TAB) material was used with experimental data of a tensile test for a more accurate simulation. The use of "engineering” and "true” stress-strain curves was pointed out.

To describe the failure behavior in tension and compression a simplified nonlinear strain-based failure criterion with linear damage accumulation (/FAIL/BIQUAD) was used to better fit the experimental response.